Martyr’s Day (January 30): Thoughts on Mahatma Gandhi

Dr. Ravi P. Bhatia

Mahatma Gandhi, one of the greatest proponents of peace and nonviolence, was shot dead by a Hindu bigot on January 30, 1948. How could this have happened has been debated and explained by scholars and the courts, which pronounced death sentences on the murderer. Many, in mourning, favored the execution. But for pacifists, the decision—rather than powerfully restraining the more vengeful excesses of Partition by graciously and mercifully demonstrating the hopefully optimistic, lovingly redemptive ideals that Gandhi stood for—merely added one more act of violence to the other. Had Gandhi survived long enough to weigh in on the ruling, perhaps he himself would not have agreed to the execution. Speaking from his deathbed, maybe he might have even provocatively called the case “a double murder.”

Mahatma Gandhi, one of the greatest proponents of peace and nonviolence, was shot dead by a Hindu bigot on January 30, 1948. How could this have happened has been debated and explained by scholars and the courts, which pronounced death sentences on the murderer. Many, in mourning, favored the execution. But for pacifists, the decision—rather than powerfully restraining the more vengeful excesses of Partition by graciously and mercifully demonstrating the hopefully optimistic, lovingly redemptive ideals that Gandhi stood for—merely added one more act of violence to the other. Had Gandhi survived long enough to weigh in on the ruling, perhaps he himself would not have agreed to the execution. Speaking from his deathbed, maybe he might have even provocatively called the case “a double murder.”

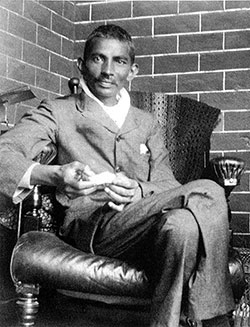

As were some others, Mohandas Gandhi was sent to the UK to study law by his rich father. He completed his law degree from the Inner Temple in London and returned to India soon after. Fate, however, had other plans for the young Mohandas. He was invited by a well-known firm (owned by Dada Abdulla), which had a shipping business, to come to South Africa. Gandhi accepted the offer and set sail in 1893. He remained in South Africa until 1914. It is said that Gandhi came to South Africa as Mohandas but went back as Mahatma.

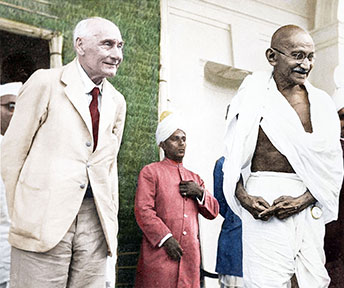

South Africa was a turning point in the life of Mohandas. He saw racism, cruelty and demeaning behavior inflicted by the British government against local and the nonwhite populations there. Gandhi himself suffered this discrimination on a few instances and developed a series of thoughts and a course of action in consultation with some scholars and religious personalities and through his correspondence with Leo Tolstoy.

South Africa was a turning point in the life of Mohandas. He saw racism, cruelty and demeaning behavior inflicted by the British government against local and the nonwhite populations there. Gandhi himself suffered this discrimination on a few instances and developed a series of thoughts and a course of action in consultation with some scholars and religious personalities and through his correspondence with Leo Tolstoy.

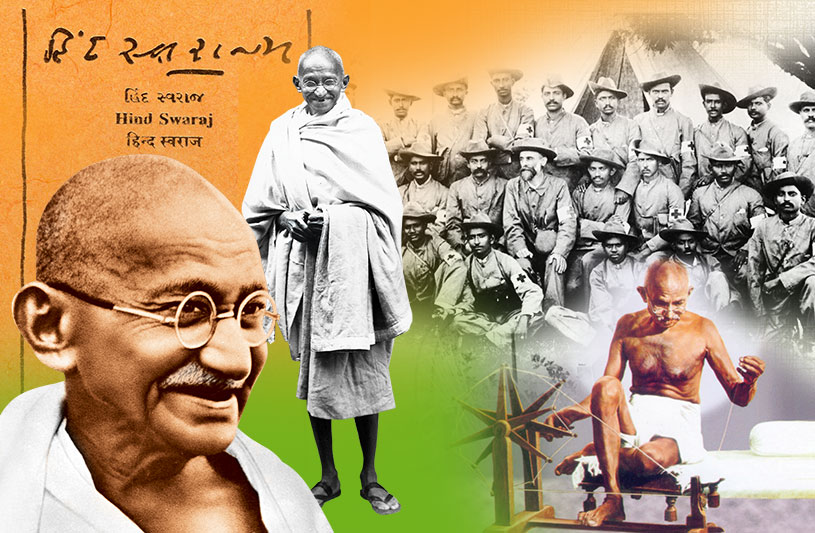

Because of these, Gandhi wrote a few pamphlets and a book, which he called Hind Swaraj (Home Rule). This small book—penned in 1909 while Gandhi was returning by ship from England to South Africa—is a masterpiece. It is worth recalling today for some of its many pertinent aspects, including its emphasis on the principle of nonviolence.

This book, which I’ll be referring to as HS (Hind Swaraj), has twenty chapters on aspects of civilization, politics, machinery, and education. Its two most important chapters—the ones which address the topics of passive resistance and swaraj—are relevant even in contemporary situations. Passive resistance or satyagraha (the word that has entered the English language) was adopted by India to free herself from British colonial rule but has been used in several other countries in Asia and Africa to help them become independent and reduce aspects of discrimination and injustice. Gandhi was also against violence in any form. Today, the anniversary of his birth—October 2nd—is known as the International Day of Nonviolence.

The British government in India had somehow seized upon an original Gujarati version of HS as supposedly being subversive. Reacting to this, he wrote “I don’t know why this has been done—there is no trace of violence in any shape or form in Hind Swaraj ….”

The British government in India had somehow seized upon an original Gujarati version of HS as supposedly being subversive. Reacting to this, he wrote “I don’t know why this has been done—there is no trace of violence in any shape or form in Hind Swaraj ….”

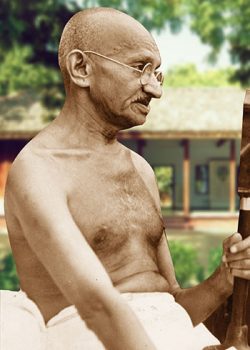

Some important aspects of satyagraha, according to Gandhi, were truth, fearlessness, poverty, simplicity, and even chastity. He also emphasized strength of purpose, not necessarily physical strength.

In South Africa, Gandhi interacted with and influenced several leaders including Nelson Mandela, Bishop Tutu, and others regarding the meaning of satyagraha. Even in the USA, Martin Luther King Jr. adopted this course of action to reduce open racism in the country. King stated that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Swaraj can broadly be interpreted as self-rule as opposed to being ruled by a foreign power. However, according to Gandhi, it also means control over one’s mind. He also strongly criticized colonization by any foreign power.

England had colonized India and many other countries around the world—in both the East and the West. It was this that led to the statement that “the sun never sets on the British Empire.” England had—through the violent means of guns, grenades, naval power, and subterfuge—colonized Australia and New Zealand and eliminated large sections of tribal people, along with their culture and their language. In the West, they had adopted similar methods to overcome the tribal populations of America and had gradually overcome the other colonial powers—Spain and France—in those North American colonies which ultimately became the genesis of the USA (when, in 1789, George Washington took the oath as the first president of the newly formed country).

England had colonized India and many other countries around the world—in both the East and the West. It was this that led to the statement that “the sun never sets on the British Empire.” England had—through the violent means of guns, grenades, naval power, and subterfuge—colonized Australia and New Zealand and eliminated large sections of tribal people, along with their culture and their language. In the West, they had adopted similar methods to overcome the tribal populations of America and had gradually overcome the other colonial powers—Spain and France—in those North American colonies which ultimately became the genesis of the USA (when, in 1789, George Washington took the oath as the first president of the newly formed country).

Gandhiji had written in HS that the removal of colonial power would not be enough unless the people who formed the government in self-rule were to adopt peaceful and harmonious policies toward the people at large and allowed local cultures, languages, and religions to flourish. He would not have been happy to note that these have all but disappeared in the countries referred to above. In Australia, there is only English for its citizens; although, in New Zealand, at least one tribal language—Maori—survives.

Fortunately in India, despite colonialism, our cultures, cuisines, languages, religious faiths, and customs survive. Gandhi had stated in HS that Hindi should become India’s national language, although people should also learn the English language.

Fortunately in India, despite colonialism, our cultures, cuisines, languages, religious faiths, and customs survive. Gandhi had stated in HS that Hindi should become India’s national language, although people should also learn the English language.

Gandhi’s ideas, his various writings, including HS and others, have influenced leaders and others across the globe.

Sometime back, I read that Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, had resigned from the office in which she served for 16 years. In the interview she gave, it shows her having led a simple life with her husband in their apartment; even cooking and washing clothes by themselves without any servants or maids. She had not shown any favors to her relatives or anyone else. She was overwhelmingly applauded by her country’s people at the time of her resignation from the office of chancellorship.

I wonder if she had been influenced by Gandhi’s ideas or writings. All kudos from an ordinary Indian to Angela!

Dr. Ravi P. Bhatia is an educationist, Gandhian scholar, and peace researcher. He is a retired professor, Delhi University. His new book, A Garland of Ideas—Gandhian, Religious, Educational, Environmental, was recently published in Delhi.