How a British royal’s monumental errors made India’s partition more painful

The midnight between August 14 and 15, 1947, was one of history’s truly momentous moments: It marked the birth of Pakistan, an independent India and the beginning of the end of an era of colonialism.

The midnight between August 14 and 15, 1947, was one of history’s truly momentous moments: It marked the birth of Pakistan, an independent India and the beginning of the end of an era of colonialism.

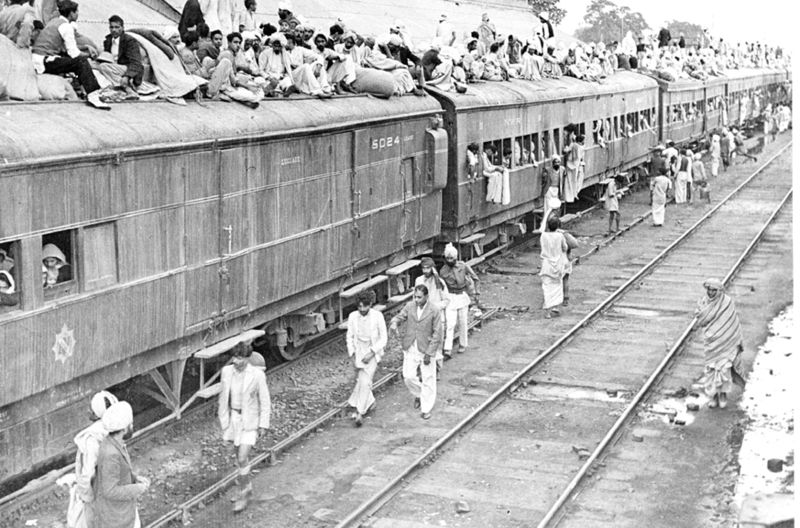

It was hardly a joyous moment: A botched process of partition saw the slaughter of more than a million people; some 15 million were displaced. Untold numbers were maimed, mutilated, dismembered and disfigured. Countless lives were scarred.

Two hundred years of British rule in India ended, as Winston Churchill had feared, in a “shameful flight”; a “premature hurried scuttle” that triggered a most tragic and terrifying carnage.

The bloodbath of partition also left the two nations that were borne out of it – India and Pakistan – deeply scarred by anguish, angst, alienation and animus.

By 1947, the political, social, societal and religious complexities of the Indian subcontinent may have made partition inevitable, but the murderous mayhem that ensued was not.

As a South Asian whose life was affected directly by partition, and as a scholar, it is evident to me that the one man whose job it was, above all else, to avoid the mayhem, ended up inflaming the conditions that made partition the horror it became.

That man was Lord Louis Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of British India.

How did Mountbatten contribute to the legacy of hatred that, 72 years later, still informs the bitter relationship between India and Pakistan?

A murderous orgy

Let us begin by recognizing the scale of barbarity that was unleashed by the mishandling of partition.

No one has captured this more poignantly than Urdu’s most prominent short story writer, Saadat Hasan Manto, who according to his grandniece and eminent historian Ayesha Jalal “marveled at the stern calmness with which the British had rent asunder the subcontinent’s unity at the moment of decolonization.”

In “The Pity of Partition,” Jalal channels the content of Manto’s work in Urdu to write:

“Human beings had instituted rules against murder and mayhem in order to distinguish themselves from beasts of prey. None was observed in the murderous orgy that shook India to the core at the dawn of independence.”

As author Nisid Hajari reports in “Midnight’s Furies,” a chilling narrative of the butchery: “some British soldiers and journalists who had witnessed the Nazi death camps, claimed partition’s brutalities were worse: pregnant women had their breasts cut off and babies hacked out of their bellies, infants were found literally roasted on spits.”

Indeed, it does not matter which was worse. What is important to understand is that partition is to the psyche of Indians and Pakistanis what the Holocaust is to Jews.

Author William Dalrymple calls this terrible outbreak of sectarian violence – Hindus and Sikhs on one side and Muslims on the other – “a mutual genocide” that was “as unexpected as it was unprecedented.”

Could the genocide have been avoided?

The violence was not, in fact, entirely unexpected. On August 16, 1946, literally a year before actual partition, a glimpse of what was to come was on display: In what came to be called “the week of the long knives,” three days of rioting in Calcutta left more than 4,000 dead and 100,000 homeless.

The hellish proportion of the slaughter that was to come was, however, unnecessary.

Well before the August of 1947, those following the tumultuous political boil in India – including U.S. Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman – fully understood that it was time for Britain – now a flailing power made bankrupt by World War II – to leave India.

As 1947 dawned, the task before the British was to find the least worst way to retreat from India: to manage the chaos, to minimize the violence and, if at all possible, to do so with some modicum of grace.

To perform this job, King George VI sent his cousin Lord Louis Francis Albert Victor (“Dickie”) Mountbatten to India as his last viceroy. This great-grandson of Queen Victoria – the first British monarch to be crowned Empress of India – was, ironically, given the task of closing the imperial shop, not just in India but around the world.

In India, he proved to be monumentally unequal to the assignment.

Mountbatten arrived in India in February 1947 and was given until June 1948 – not 1947 – to complete his mission. Impatient to get back to Britain and advance his own naval career, he decided to bring forward the date by 10 months, to August 1947 (he eventually did become first sea lord, a position he coveted because it had been denied to his father).

How crucial were those 10 months?

I would argue, they could have meant the difference between a simply violent partition and a horrifically genocidal partition.

A hurried drawing of border lines

The context for a bloody partition was set with the decision to sever Bengal in the east and Punjab in the west in half – giving Jinnah what he called a “moth-eaten Pakistan.” That killed any hopes of a federated India, which was Jinnah’s preference, if it allowed for power sharing and autonomy to Muslim majority provinces.

To decide the fate of 400 million Indians and draw lines of division on poorly made maps, Mountbatten brought in Cyril Radcliffe, a barrister who had never set foot in India before then, and would never return afterwards. Despite his protestations, Mountbatten gave him just five weeks to complete the job.

All of India, and particularly those in Bengal and Punjab, waited with bated breath to find out how they would be divided. Which village would go where? Which family would be left on which side of the new borders?

Working feverishly, Radcliffe completed the partition maps days before the actual partition. Mountbatten, however, decided to keep them secret. On Mountbatten’s orders, the partition maps were kept under lock and key in the viceregal palace in Delhi. They were not to be shared with Indian leaders and administrators until two days after partition.

Jaswant Singh, who later served as India’s minister of foreign affairs, defense and finance, writes that at their moment of birth neither India nor Pakistan “knew where their borders ran, where was that dividing line across which Hindus and Muslims must now separate?”

He adds that as feared and predicted, this had “disastrous consequences.” The uncertainty of exactly who would end up where fueled confusion, wild rumors, and terror as corpses kept piling up.

As historian Stanley Wolpert writes in “Shameful Flight,” Mountbatten kept the partition maps a closely guarded secret, as he did not want the festivities of British transfer of power to be marred or distracted.

“What a glorious charade of British Imperial largesse and power ‘peacefully’ transferred,” lamented Wolpert as he contemplated the possible implications of Mountbatten’s hubris.

70 years later

As the preeminent biographer of all the major political actors of British India’s last days, Wolpert acknowledges that many – and, most importantly, Indian political leaders themselves – contributed to the chaos that was 1947.

But there is no room for doubt in Wolpert’s mind that “none of them played as tragic or central a role as did Mountbatten.”

By botching the administration of partition in 1947 and leaving critical elements unfinished – including, most disastrously, the still unfinished resolution to Jammu and Kashmir – Mountbatten’s partition plan left the fate of Kashmir undecided.

Mountbatten, thus, bestowed a legacy of acrimony on India and Pakistan.

It was not just rivers and gold and silver that needed to be divided between the two dominions; it was books in libraries, and even paper pins in offices. As Saadat Hasan Manto’s fictional account conveys, the madness was such that even patients in mental hospitals had to be divided.

Yet, Mountbatten, the man who would fret incessantly about what to wear at official ceremonies, made little effort to devise arrangements for how resources would be divided, or shared.

Learning from history

Nowhere does the unfinished business of partition bleed more profusely than in the continuing conflict between India and Pakistan over Jammu and Kashmir.

Would a little more attention and a few more weeks of effort in 1947 have spared the world a nuclear-tipped time bomb that keeps ticking on both sides?

We can never know the answer to this question.

Nor can, or should, I believe, India and Pakistan blame the British and Mountbatten for all their problems. Seventy-two years on, they have only themselves to blame for missing opportunity after opportunity to fix the troubled relationship they inherited.

However, maybe, today, on the anniversary of their birth, both India and Pakistan can take a break from simply bashing each other and recognize that at times history can deal you a bad hand in many different ways – in this case, due to the hasty and monumental errors of a British royalty. But also recognize, it is on you to learn from history and fix it.

This piece was first published on August 15, 2017 and was updated to reflect the 72 years of partition of India and Pakistan.

About the Author

Prof. Adil Najam is Dean of The Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University, where he is also a Professor of International Relations and of Earth & Environment. Earlier, he has served as Vice Chancellor of Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) in Lahore, Pakistan; and as Director of the Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future at Boston University.

Prof. Adil Najam is Dean of The Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University, where he is also a Professor of International Relations and of Earth & Environment. Earlier, he has served as Vice Chancellor of Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) in Lahore, Pakistan; and as Director of the Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future at Boston University.

Prof. Najam was a co-author for the Third and Fourth Assessments of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); work for which the scientific panel was awarded the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize for advancing the public understanding of climate change science. In 2008 he was invited by the United Nations Secretary General to serve on the UN Committee on Development (CDP). In 2010 he was awarded the Sitara-i-Imtiaz (Star of Excellence), one of Pakistan’s highest civil awards by the President of Pakistan.

Prof. Najam has written nearly 100 scholarly papers and book chapters, and his recent books include: South Asia 2060: Envisioning Regional Futures (2013); How Immigrants Impact their Homelands (2013); The Future of South-South Economic Relations (2012); Trade and Environment Negotiations: A Resource Book (2007); Envisioning a Sustainable Development Agenda for Trade and Environment (2007); Pakistanis in America: Portrait of a Giving Community (2006); Global Environmental Governance: A Reform Agenda (2006);Environment, Development and Human Security: Perspectives from South Asia (2003); and Civic Entrepreneurship (2002). Prof. Najam is frequently interviewed by and writes for the popular media and is the founding editor of the award-winning blog Pakistaniat.com (voted the Best Current Affairs Blog in Pakistan (2010) and also won the 2010 Brass Crescent Award for Best Muslim Blog from South Asia)..

He is a past winner of MIT’s Goodwin Medal for Effective Teaching, the Fletcher School Paddock Teaching Award, and the Stein Rokan Award of the International Political Science Association, the ARNOVA Emerging Scholar Award, and the Pakistan Television Medal for Outstanding Achievement. In 2011, he was elected a Trustee on the International Board of WWF; and in 2013 elected a Trustee of The Asia Foundation (TAF). He has been a Council Member of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) in Vienna, Austria; and is the Board Chair of the South Asia Network of Development and Environmental Economics (SANDEE). Dr. Najam has also served on the Academic Council of the South Asian University (SAU), New Delhi, India and the Syndicate (Board) of the University of Engineering and Technology (UET), Lahore, Pakistan. He continues to serve as a Board’s Visiting Committee member at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).