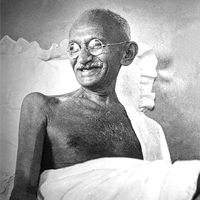

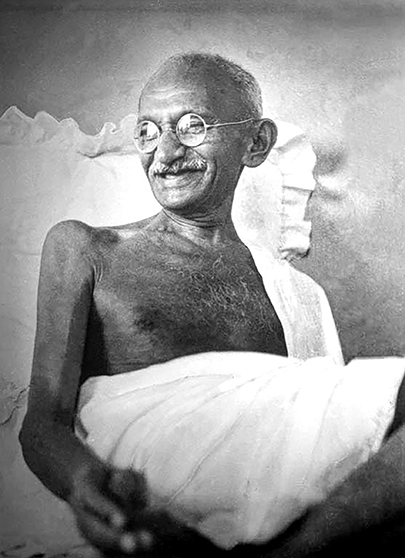

Gandhi, the Philosopher

By Raj Shah

Commemorating Gandhi Ji on his birth anniversary, October 2nd, widely recognized as Gandhi Jayanti in India.

“People often remember Gandhi, one of the most celebrated figures of the 20th century, for his role as a political leader who guided India toward independence through non-violence.” However, his contributions to philosophy are equally significant and deserve recognition in their own right. Unlike many traditional philosophers, Gandhi did not engage in abstract metaphysical inquiries but instead focused on ethics as a way of life. We can understand Gandhi’s philosophical thought as an ethics-led philosophy, akin to the teachings of Buddha and Socrates.

Gandhi as an Ethics-Led Philosopher

There are two major streams in philosophy: metaphysics-led and ethics-led philosophies. Metaphysics-led philosophies emphasize understanding the ultimate reality and often involve some form of communion with a higher truth.

There are two major streams in philosophy: metaphysics-led and ethics-led philosophies. Metaphysics-led philosophies emphasize understanding the ultimate reality and often involve some form of communion with a higher truth.

On the other hand, ethics-led philosophies focus on transforming the individual’s state of being from a lower, baser state to a higher ethical one, aiming to cultivate virtues and self-sufficiency. Gandhi’s philosophy, like that of the Buddha and Socrates, falls into the ethics-led category.

In Gandhi’s ethical worldview, the reduction of self-centeredness is a key trait. For Gandhi, ethical living was not merely about individual moral behavior but was intrinsically connected to the well-being of all. He called this concept “sarvodaya,” meaning the welfare of all.

Gandhi’s focus on ethical living was also a pathway to psychological self-sufficiency, where selfish fears and desires dissolve. Much like the Buddha’s concept of Nirvana, Gandhi’s ultimate ethical goal was to attain moksha, or liberation from selfishness and suffering.

Ethics Over Metaphysics

Gandhi’s rejection of metaphysical inquiries in favor of ethical transformation aligns him with ethical consequentialism. This concept judges the ethical value of an action based on its outcomes, especially the reduction of self-centeredness and the promotion of the common good. This approach set Gandhi apart from other philosophical traditions that prioritize metaphysical knowledge over ethical practice. In his lifetime, Gandhi constantly worked to eliminate selfish thoughts and behaviors, seeking to achieve what he referred to as a state of “zero”—a complete absence of selfishness. Only through this transformation could one truly benefit all, he believed.

In his translation of the Bhagavad Gita, Gandhi highlighted this ethical focus by famously shifting from the belief that “God is Truth” to “Truth is God.” This subtle yet profound shift underscored his conviction that ethics, not metaphysics, should be the foundation of philosophy. Gandhi also drew his ethical framework from William Salter’s Ethical Religion, a proposal that views morality as a form of religion. By this, Gandhi meant that ethical practice should be central to spiritual life, not metaphysical beliefs.

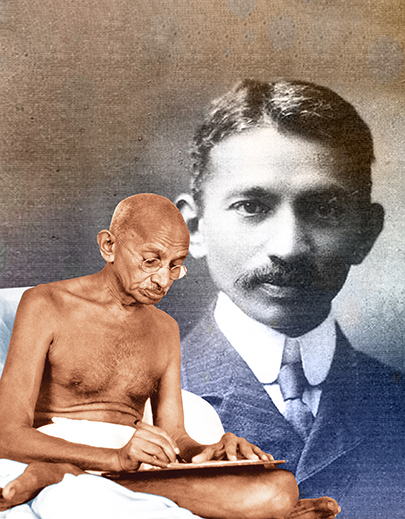

Satyagraha and Truth is God

Mahatma Gandhi has interpreted various concepts of metaphysics, political and social philosophy, alongside moral and religious philosophy. While Gandhi may not have introduced any entirely new doctrines, his interpretations of various philosophical concepts—such as truth, God, non-violence, and satyagraha—are substantial enough to consider him a philosopher, and Gandhism as a philosophy. Gandhi’s metaphysical ideas are evident in his views on truth, God, and the soul or mind. He did not view truth as merely an attribute of God; rather, he believed that God is Truth, leading him to assert, “Truth is God.” Gandhi was a humanist, holding the belief that man is God’s greatest creation and that God resides within man. His philosophy of religion offers a fresh perspective on religious thought, showcasing his religious tolerance and belief in the value of all religions. Gandhi also laid out moral principles aimed at developing man’s ethical personality.

A Socialist Vision

Gandhi’s philosophy extended beyond individual ethical behavior to encompass broader societal structures. His ethical framework led him to advocate for socialism, which he saw as the only logical outcome of an ethics-led philosophy. In Gandhi’s view, capitalism, with its inherent encouragement of selfishness and material accumulation, was antithetical to the ethical life he espoused. Instead, he envisioned a society where the principles of equality and the absence of private property would minimize selfishness.

Gandhi’s philosophy extended beyond individual ethical behavior to encompass broader societal structures. His ethical framework led him to advocate for socialism, which he saw as the only logical outcome of an ethics-led philosophy. In Gandhi’s view, capitalism, with its inherent encouragement of selfishness and material accumulation, was antithetical to the ethical life he espoused. Instead, he envisioned a society where the principles of equality and the absence of private property would minimize selfishness.

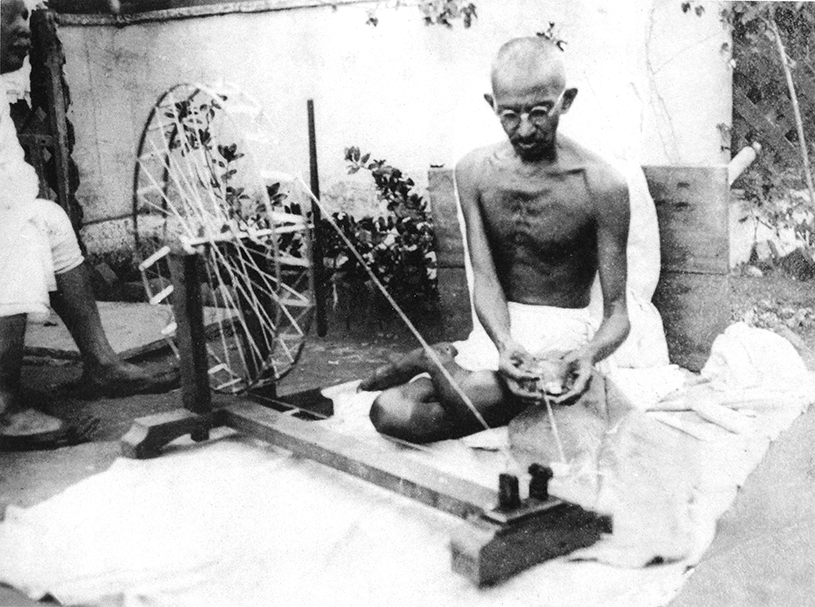

Gandhi’s concept of swaraj, or self-rule, was not just about political independence but also about creating self-sustaining, ethical communities that would serve as socialist enclaves within a capitalist world. Gandhi designed his ashrams as socialist communes, prioritizing the principles of simple living, collective welfare, and ethical practice. These communities, according to Gandhi, were to serve as models for a future society in which ethical living would be the norm.

Ahimsa or Non-Violence

“Gandhi’s ethical philosophy deeply rooted his approach to political action. His concept of non-violence, or ahimsa, was not just a political strategy but a way of life that reflected his commitment to the welfare of all beings. “

“Gandhi’s ethical philosophy deeply rooted his approach to political action. His concept of non-violence, or ahimsa, was not just a political strategy but a way of life that reflected his commitment to the welfare of all beings. “

Ahimsa, for Gandhi, was the highest ethical principle, and it was through this lens that he approached political struggles. Gandhi demonstrated that one should never compromise ethical principles for expediency, even in the pursuit of political goals, by refusing to harm others.

Gandhi’s non-violent resistance also exemplified ethical activism. He believed that a practitioner of this philosophy could work for the betterment of society while simultaneously transforming themselves ethically.

In this way, Gandhi’s philosophy was both personal and political, aiming to create a just society through the transformation of individuals. His vision of non-violent resistance remains one of his most lasting contributions to philosophy, offering a pathway for ethical political engagement in a world often dominated by violence and selfish interests.

Philosophy as a Way of Life

The shift in the understanding of philosophy since the Enlightenment has led to the overlooking of Gandhi’s philosophical significance. People practiced philosophy as a way of life in ancient times, particularly in India, China, and Greece. It was not just an academic discipline, but rather a lived practice that involved the cultivation of virtues and the pursuit of ethical living. Over time, however, Western philosophy began to move away from this practice-oriented approach, becoming increasingly theoretical and abstract.

The 18th century solidified this shift by largely confining philosophy to academic institutions. As a result, the idea of philosophy as a way of life faded in the West. Gandhi’s ethical philosophy, deeply rooted in the practice of ethical living, did not align with the modern Western conception of philosophy. For this reason, people often remember Gandhi as a political leader rather than a philosopher.

However, the recognition of Gandhi as a philosopher is gradually gaining ground, thanks to scholars like Akeel Bilgrami and Richard Sorabjee, who have drawn attention to the philosophical dimensions of his thought. By framing Gandhi’s life and work within the broader tradition of ethics-led philosophy, these scholars help to position him alongside figures like the Buddha, Socrates, and Confucius, whose philosophies were similarly grounded in ethical practice rather than metaphysical speculation.

Gandhi’s Legacy as a Philosopher

Gandhi’s philosophy, while deeply political, was also profoundly ethical. Gandhi’s vision was to replace individual self-centeredness with concern for the well-being of all, a vision he pursued through both personal ethical practice and political activism. Gandhi’s commitment to non-violence, equality, and ethical living places him within a long tradition of ethics-led philosophy, making him a figure of immense philosophical importance.

By reinvigorating the ancient tradition of philosophy as a way of life, Gandhi offers a vision of how philosophy can once again serve as a guide for ethical living, not just for individuals but for societies as a whole. His emphasis on ethics over metaphysics, his rejection of capitalism in favor of socialism, and his belief in the transformative power of nonviolent action remain as relevant today as they were during his lifetime. In this way, Gandhi’s legacy as a philosopher endures, offering a model of ethical living that transcends the boundaries of time, culture, and politics.

About the Author:

A software engineer by profession, Indian culture enthusiast, ardent promoter of hinduism, and a cancer survivor, Raj Shah is a managing editor of Desh-Videsh Magazine and co-founder of Desh Videsh Media Group. Promoting the rich culture and heritage of India and Hinduism has been his motto ever since he arrived in the US in 1969.

A software engineer by profession, Indian culture enthusiast, ardent promoter of hinduism, and a cancer survivor, Raj Shah is a managing editor of Desh-Videsh Magazine and co-founder of Desh Videsh Media Group. Promoting the rich culture and heritage of India and Hinduism has been his motto ever since he arrived in the US in 1969.

He has been instrumental in starting and promoting several community organizations such as the Indian Religious and Cultural Center and International Hindu University. Raj has written two books on Hinduism titled Chronology of Hinduism and Understanding Hinduism. He has also written several children books focusing on Hindu culture and religion.