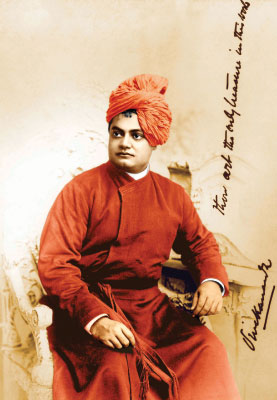

My Tribute to Swami Vivekananda

Author by Professor Nathan Katz, PhD, Florida International University

The World Hindu Council hosted an Interfaith Dialogue at the University of Miami to commemorate Swami Vivekananda’s 150th birth anniversary celebration. The following speakers participated in this dialogue: Dr. Nathan Katz representing the Jewish religion, Vijay Raghavan representing the Hindu religion, Rev. Dianne Hudder representing the Christian religion, Mohammad S. Shakir representing the Muslim religion, Major Diljit D Singh Pannu representing the Sikh religion and The Venerable Phra Suputh Kosalo (Supat) Representing the Buddhist religion

Desh-Videsh will print excerpt of each speaker’s speech over the next few issues. Below is an excerpt of Dr. Katz’s speech.

The impact of Swami Vivekananda on modern India is, of course, profound. But it might not be quite so widely appreciated that he also helped to shape contemporary American spirituality.

Born in 1863, Vivekananda was a strapping youth, educated in the British traditions of Kolkata, became a Freemason, and then joined the rationalist, socially engaged Hindu movement founded by Ram Mohan Roy a century before, the Brahmo Samaj. But he found these traditions to be overly intellectual, so he sought out the highly respected mystic, Sri Ramakrishna, at his Dakineshwar Temple at Kalighat, then a small village near Kolkata. Vivekananda was skeptical when he asked Ramakrishna whether he had seen God, to which the saintly, humble man replied, “Yes, I have seen God just a surely as I see you, but more clearly.” Not too long after, Vivekananda received Shakti pad (“energizing touch”) that evoked the mystical condition known as nirvikalpa samadhi, “thoughtless concentration” or the bliss of union. He became a renunciate under Ramakrishna’s tutelage, and succeeded him as head of a monastic order he named for his guru, the Ramakrishna Order. Vivekananda travelled the length and breadth of India, preaching neo-Vedanta, a mystical monism coupled with social activism.

When he was thirty, he made his way to Chicago for the World Parliament of Religions, which invited only Christians and a coupleof Jews. At that time, American intellectuals were familiar with Indian philosophy via translations of classical texts, but they had never seen a living Hindu before, much less this charismatic swami. His countenance and his saffron robes and turban startled them, and after initial difficulties, he was permitted to address the Parliament on September 11, 1893, exactly 108 years before the American defining moment when jihadi terrorists attacked New York City. Vivekananda died on July 4, 1902, the birth date of the United States.

His address was an overwhelming success; it would be no exaggeration to say he was the start of the proceedings. He preached a unity of the religions of the world, demonstrating the spirit of tolerance that he said characterized Hinduism. His use of Adishankara’s analogy of rivers merging upon reaching their destination in the ocean to symbolize the underlying unity of the divine goal of all religions was both surprising and uplifting to his audience. I also note with satisfaction that he mentioned the lovely Paradesi Synagogue in Kochi, where my wife and I prayed for a full year.

His address was an overwhelming success; it would be no exaggeration to say he was the start of the proceedings. He preached a unity of the religions of the world, demonstrating the spirit of tolerance that he said characterized Hinduism. His use of Adishankara’s analogy of rivers merging upon reaching their destination in the ocean to symbolize the underlying unity of the divine goal of all religions was both surprising and uplifting to his audience. I also note with satisfaction that he mentioned the lovely Paradesi Synagogue in Kochi, where my wife and I prayed for a full year.

Vivekananda has been hailed as “the father of modern interreligious dialogue,” and this is more or less correct. Before his time, on the rare occasions when religions met, it was to debate and dispute. In a debate, we come to prove the other wrong and ourselves right. But in dialogue, we come to learn from the other and thereby broaden our spiritual and intellectual horizons. Vivekananda summarily heralded this new approach.

He was perfect for his time. In the past century, circumstances have changed, and most of us now feel secure in open-heartedly honoring all religions, a far cry from the triumphalism of evangelization that he encountered in India. We are, in fact, sufficiently secure today that interreligious dialogues may concentrate on differences as well as commonality.

He was perfect for his time. In the past century, circumstances have changed, and most of us now feel secure in open-heartedly honoring all religions, a far cry from the triumphalism of evangelization that he encountered in India. We are, in fact, sufficiently secure today that interreligious dialogues may concentrate on differences as well as commonality.

Just for one example: Generally speaking, Hindus see unity as the Divine Reality. For the most part, we Jews praise God for making distinctions, that holiness is to be found in a divine diversity. The Kabbalistic vision of a redeemed world likens the different religions to the organs of the body. A heart is not a kidney, but the heart and kidney are mutually dependent. Bodily health requires the coordination of the various organs, just as, this analogy would hold, a healthy planet depends on Hindus and Jews, Muslims and Jains, Christians and Buddhists, affirming both their distinctiveness and their mutual dependence. Today, we do not need to agree to appreciate and celebrate the glorious diversity that we hold is an essential part of God’s plan for all of us.

About the Author

About the Author

Nathan Katz is a research professor at the School of International and Public Affairs at Florida International University. Professor Katz is also a Bhagwan Mahavir Professor of Jain Studies.